道一风同

徐芸

记得以前外公(聂其焜)房间的书架上并排放着三本相同的英文书,书名是“Doctors East, Doctors West”书脊下面还有这本书的中文名 “道一风同”。我一直没有抽时间阅读,之后这三本书在文革时消失了。

到美国后,三阿姨(聂光琼)告诉我这本书中有关于聂家的故事。我托人弄到了这本书,读到太公(聂辑椝)在长沙病重,Hume 医生出诊为他看病之记载。

书的作者是Edward H. Hume,中文名胡 美 (1876 – 1957)。他1897年毕业于耶鲁大学,1901年从约翰霍普金斯大学获医学博士。1905 年应耶鲁大学雅礼学会邀请来中国,在长沙创办雅礼医院并任院长,教务长。1914年创始湘雅医学院。1927年回美国。

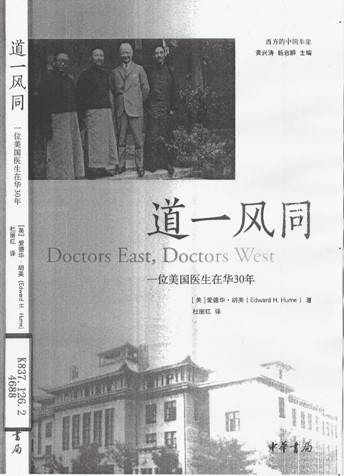

此书1946年在美国出版,副标题是“一个美国医生在中国的经历”,亦是作者的自传。书封皮上的中文名“道一风同”是胡 适博士,当时中国驻美大使题的字。虽然这本书已绝版,亚马逊网购站尚还有几本待购。在我整理材料期间,得知中国在2011年出版了此书的中文翻译本,书名为“道一风同”,共印3,000本。在中文的亚马逊网站上有售。封面上有我外公的照片。

|

|

|

|

英文版的《Doctors East, Doctors West》,中文书名为当时的驻美大使胡适所提。

|

保存在上海图书馆的中文译本的封面,由中华书局出版。

|

Hume 医生去世后不久,他的同事,朋友和家人集资成立了Edward H. Hume 纪念讲座,每年请一名世界著名东亚学者在耶鲁大学演讲至今。1960年的演讲者是哈佛大学汉学权威费正清教授 (John Fairbank)。

现我将部分章节用中文介绍给各位,同时也将英文原文列在后面,供参考。

随着湘雅医院的影响在城里扩大,我们去长沙显贵人家的次数也越来越多。浏阳门街的聂公馆就是其中之一。我(胡 美医生)以前去过他们的公馆多次,都是社交活动,他们家的庭院里种了花草,优雅的客厅里有黑檀木的家具,墙上挂着宋朝风格的丝绸画卷。但是这次我是被请去看家族的首领,年迈的官员本人。

聂总督最近才辞去沿海两省的最高职务回到家乡。由于身体欠佳,他在家宅中静养。他的四儿子(聂其焜)在上海曾跟私人教师学过英文,和我最熟。他常常与我说起他父亲头晕和出鼻血,所以我对这次急诊不是完全没有准备。

我是由聂总督的官轿接到聂公馆的,我们绕过精雕的龙墙进入大门。到主会客厅时他的七个儿子已站着迎候。看到我,他们都按中国习惯鞠躬行礼,只有三儿子(聂其炜)和四儿子,因为与我很熟除了鞠躬外还与我握手。三儿子作为代言人用中文说话,以便其他人可以听懂。“我们的父亲突然病了,前天他在院子里走路,绊了一跤,就此昏迷。目前他仍然昏迷不醒,病情每个小时在加剧。湖南最有名的两个医生已来看过他,都认为他病情十分严重。四儿子和我说服大家请你来会诊,你也知道他们相信中医。而我们俩认为父亲也应该试试西医。能否请你去他卧室给他诊断一下?”

我跟着三儿子,和其他六个儿子一起去病人房间。病人由两边两个佣人扶着坐在床上。当地人都相信病人如果平躺在床上,会使身体与精神脱离,对病人不利。为使身体和精神在一起,就要让病人坐起。

我一走进这黑黑的屋子,就知道病人得的是什么病了:呼吸慢而重,深度昏迷,无疑脑血管破裂了。我到病人旁边,先小心地按他右边的脉,按了很长时间,再按左边。接着检查他的舌,瞳孔,四肢,肌肉无力,等等。我注意到他的七个儿子都对我的细心检查,尤其是检查舌和脉搏很满意。他们也高兴地看到我用体温计。我作病历记录时,他们在互相交谈。检查完毕,代言人问我诊断结果。“你们的父亲中风了。”七个兄弟异口同声说:“对。”很明显他们是陪审员,我只是法庭上的一个旁证。对我来说这是第一堂生动的课,一个中国家庭全权控制诊断和决定。代言人接着问:“你觉得应该怎么办呢?”“你们知道他的中风是因为脑子里有根动脉破了,我们应该想法减少他脉搏的压力。”

话后大家议论开了。“有谁听说过给一个重病人减轻脉搏的力量?”一个保守的儿子说,“强有力的脉搏是生命的保证。”

这时四儿子开始插话,他和我是好朋友,互相信任。他说:“也许胡医生说的话有根据。”我很感激他为我说话。因为我总是随身带着一本由英文翻译成中文的西医书,我翻到有关的一页,递给他们看。这本西医书从来没有被人像这七个兄弟这样仔细地阅读过,其中两个兄弟同意西医的看法,其他五个仍持怀疑态度,不愿相信。他们看了我推荐的治疗方法:头放平,身体保暖,灌肠。

代言人三儿子问道:“你要给病人开药吗?”因为我是他主张请的医生,他希望他的家人不要减少对我的信任,而切我能有惊人之举。

我开了泻药,并向他们作了详细的介绍。他们都清楚汞是泻药,因为中医书也这么说。但是最高仲裁人不是他们(陪审员),而是他们的母亲。四儿子将药方送到女人住区,很快就高高兴兴地回来了。他说服了他们的妈妈采用此药和我提出的护理方法。临走前,我又叮嘱几句,答应会尽快派个医院的护理工来他们家,然后鞠躬退出大门。在前院我又转身鞠躬,七个儿子也都鞠躬回礼。至少有两个兄弟对我特感激。

四儿子将我送到轿子旁,说愿意今后与我多来往,或是找我看病,或是朋友互访。“你不要因为我们的保守而退却。但愿我们的妈妈会同意让你的护工来此按你的指示照看我们的父亲。恐怕我们父亲这次的病无法医治了,但是我们知道你尽了力。”

三天后聂总督去世,但是我与聂家的友谊保持了下来。我收到公开葬礼的请柬,我也按惯例送了白条幅,称颂去世的总督的功绩,也是表示哀悼的形式。接下来的三年,所有的儿子都穿粗麻丧衣,辫子里也编上粗麻布条。这三年内家中不设宴请,母亲带着七个儿子和几个女儿在家过着低调的日子。

注:因为大外公英年早逝,我认为“三儿子”是四外公,“四儿子”是我外公。

书中还提到湘雅医院,医学院的名称是怎么来的:

1913年夏我们开会讨论给新的医学院起什么名字。我们的老朋友,聂先生提议:“名字很重要,我们提倡湖南人民和耶鲁大学雅礼协会合作。湖南省的别名是湘,耶鲁雅礼协会的第一个字是 “雅”,我们就起湘雅这个名字吧!听到这个名字人们就知道这是湖南-耶鲁。”

这个名字符合我们的要求,“湘”是流经湖南中部的一条河流,河两旁的自然景色优美。而中国人也喜爱名字中有山水的含义。因此以后医院,医学院,护士学校都叫湘雅。

以下为英文原文

Page 183

As the influence of the hospital spread through the city, we were called more and more frequently by the families of the influential old officials who were the aristocracy of Changsha. The Nieh family who lived in the great mansion on Liuyang Gate Street was one of these. I had often paid social visits to the magnificent establishment and enjoyed the flower-decked courtyards, the gracious reception halls with their stately blackwood furniture, and the wall paintings on silk scrolls, done in the style of the Sung Dynasty; but on this day I was summoned to see the old official himself, the head of the clan.

Governor Nieh had but recently returned from the highest official posts in two of the seacoast provinces. On account of failing health he had been living quietly at his town home. Brother Four, who had studied English with private tutors in Shanghai, was the son I knew best. He had often talked to me about his father’s fainting spells and attacks of nosebleed, so I was not unprepared for this emergency call.

The Governor’s official sedan chair had been sent to fetch me. We swung in through the great gateway, round the gorgeous dragon screen. In the main reception hall, the seven brothers stood waiting to receive me. All of them greeted me with ceremonial Chinese bows, but Brothers Three and Four, whom I knew so well, shook hands with me also. Brother Three acted as spokesman, addressing me in Chinese, so that all might understand. “Our father was taken ill suddenly. He was walking in the garden, day before yesterday, when he stumbled, fell, and became unconscious at once. He remains unconscious now, and his condition grows more serious every hour. Two of the most distinguished physicians in Hunan, Doctor Wang and Doctor Lei, have already examined him. Both of them agree that the outlook is exceedingly grave. Brother Four and I persuaded our five brothers to send for you. As you probably know, they have great confidence in Chinese medicine. We two believe that Western medicine also should be tried for our father. Will you go with us and examine him in the inner bedroom?

Following Brother Three and accompanied by the other six, I made my way to the patient’s room. He was propped up by two servants who sat beside him on the bed. This was a universal practice, it being believed that the more fully supine a patient lay in bed, the worse the outlook. Everything was done to persuade the body and spirit to stay together. To have the patient lie quite flat would be to invite dissolution.

The diagnosis was evident the moment I entered the darkened room: slow, stertorous breathing, deep coma. Undoubtedly there was a ruptured blood vessel in the brain.

I took my place by the patient and examined the pulse carefully and long, first on the left wrist, then on the right. Tongue, pupils, extremities, loss of muscular power, and all the other signs were noted. I observed that the seven brothers were all quite impressed with my care, especially with my detailed observations of tongue and pulse. There were glad, too, that I was using the thermometer. I heard them comment to each other as they saw me record my findings on a history card. When I was through, the spokesman asked whether I had made a diagnosis.

“Your father has had a stroke of apoplexy – chung feng, you call it.”

With one voice, the seven brothers called out, “Correct!”

Clearly they were the jury – I merely a witness put on the stand. It was my first vivid lesson as to the complete control by a Chinese family over diagnosis and decision.

“What procedure do you recommend?” the spokesman continued.

“You understand that this ‘stroke’ is undoubtedly due to a breaking of one the arteries in the brain. We should do all we can to reduce the pressure of his pulse.”

That caused a commotion. “Who ever heard of weakening the pulse strength in a dangerously ill patient?” one of the conservative brothers challenged. “A strong pulse is the one sure guarantee of life.”

At this point Brother Four broke in. He and I had become good friends, with great mutual confidence in each other. “Perhaps,” he said, “Doctor Hume has some classical authority for his position!”

I was grateful enough, both for the championing of my cause and, more particularly, for the fact that I had taken along in my medical bag, as always, a Chinese translation of Osler’s Practice of Medicine. I turned to the relevant page and handed the book over. Sir William Osler never had more attentive readers than those seven brothers, two ready to accept that dicta of a Western physician, and the other five skeptical, almost scornful.

They read of the procedure I was recommending: the head was to be lowered, the body to be kept warm, a high enema to be given.

“Will you not prescribe some drug?” the spokesman inquired, hopeful that I, his nominee, would not undermine his family’s confidence in me. He wanted me to do something really dramatic.

I wrote a prescription for a purgative, and described it to them carefully. They knew all about mercury as a cathartic for they had read about it in the writings of their own physicians. Yet the decision lay, not with this jury, but with their mother, who was now the final arbiter. The prescription was taken back to the women’s apartments by Brother Four, who returned presently, elated that he had persuaded her to approve both the drug and the entire course of action I had outlined. I gave some further instructions, promised to send over a hospital orderly as soon as possible, and bowed my way out to the great front gate. In the front courtyard I turned to bow again and be bowed to by the seven brothers. Two of them, at least, were particularly grateful for my visit.

Brother Four escorted me personally to the sedan chair and said that he would count on seeing me often, both professionally and as a personal friend. “You must not let the conservatism here discourage you. I hope our mother will be willing to have your orderly come over and stay here to carry out all your instructions. I fear my father will not survive this stroke, but we know you have done all that was possible.”

Governor Nieh died three days later, but our friendship with the family continued unbroken. I received the formal invitations to the public service of mourning and responded by sending the conventional white scrolls, inscribed with tribute phrases honoring the deceased leader. This was the correct way to express condolence.

The brothers all wore coarse hempen mourning robes, and strands of coarse hempen thread were braided into their queues, to remain for three full years. There was no feasting during those years; the mother and her seven sons, as well as the several daughters, remained quietly at home.

Page 177

In the summer of 1913, the Yale University Mission in Changsha and the newly constituted Chinese Society for the Promotion of Medical Education set up a joint board with ten members from each group. We were wondering what name to give the new enterprise when our old friend, Mr. Nieh, made a suggestion. “The matter of a name is very important. We are proposing a co-operation between citizens of Human and the Yale University Mission. The literary name of our province is Hsiang. The first syllable of the name of the Yali Mission is Ya. Let us call our united body the Hsiangya Medical Educational Association. Everyone who hears that name will recognize that this means Hunan –Yale.”

The name conveyed just the meaning we desired. Hsiang was the name of the central river of the province, a waterway of great natural beauty. Our Chinese friends always welcomed a name that savored of mountains or rivers or lakes. The hospital, the medical school, and the school of nursing have, ever since then been known by the name of Hsiangya.